By David Rogers. BLOWING ROCK, N.C. — Call landscape architect and golf course designer Ron Cutlip a “people pleaser,” if you will. Like when he sees kids playing on the Blowing Rock School playground he designed, he relishes the moment when he witnesses people enjoying his creations as intended.

That’s just one of the discoveries enjoyed on Sept. 4 by more than 60 members and guests of the Blowing Rock Garden Club in a presentation hosted by the Blowing Rock Art & History Museum.

The Land Whisperer

For Cutlip, landscape architecture is art. A piece of land, whether grassy knolls or wooded forests, is his blank canvas — and like one of his mentors, pioneer American real estate developer James Rouse, he always has people in mind.

Beginning his powerpoint presentation with Rouse’s influence on his work, Cutlip reflected on Rouse’s proposed planned community in Columbia, Maryland, which he envisioned as “… a garden for growing people.”

“I listen to the land,” Cutlip told the crowded Community Room audience. “It tells me what it wants to be, what it wants to say, what it wants to feel, what it wants to share and what it wants to solve.”

Beginning when he was nine years old, Cutlip said he was pretty sure he wanted to be a landscape architect and, through the years, he has had both mentors as well as what he described as, “influences.”

A member of the American Society of Landscape Architects, Cutlip flipped from slide to slide in his powerpoint presentation, describing those influencers and how his studies of their careers eventually impacted his own work: James Rouse, Roberto Burle Marx, and Thomas Church. Of the three, Cutlip said he was lucky to have met one of them, Rouse, “… and I found him to be the perfect gentleman.”

Cutlip never met Roberto Burle Marx, a Brazilian landscape architect whose designs of parks and gardens made him world famous, but his influence on Cutlip was nonetheless striking. Credited with introducing modern landscape architecture to his native country, Brazil, Marx was known as a modern nature artist and public space designer.

For Cutlip, Marx’s visionary thinking provided inspiration for always keeping people in mind because people are at the core of civilization.

“The garden is — must be — an integral part of civilized life: a deeply felt, deeply rooted spiritual and emotional necessity,” Marx once said in The Garden as a Form of Art, a 1962 lecture.

Whether designing a backyard space or a garden adjacent to a 30-story building in the middle of New York City, Cutlip places a keen importance on the garden as a place for people to study, to reflect, to think.

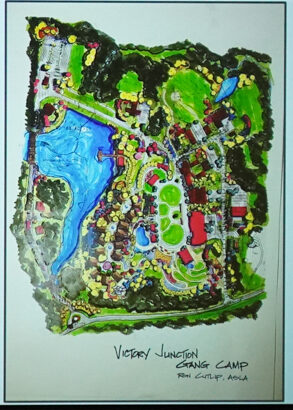

Landscapes can also provide a space for children to play, such as the Victory Junction Gang Camp Cutlip designed for Richard Petty, a camp for kids challenged by disabilities, serious illnesses, or other special needs.

Giving Credit

Being influenced by another’s work is different than copying them.

“I don’t copy anyone else,” said Cutlip. “But you can see from some of my work and how the patterns and colors used in my designs have similarities with these three recognized masters, certainly they influenced my work. In anything, as you study and learn a profession some of the things you studied emerge in your own work.”

Cutlip was especially complimentary of the Blowing Rock Garden Club’s work in making the stretch of sloped earth along Main Street, just below Memorial Park, one of the most talked about parts of people’s visits to the High Country.

“That garden along Main Street is No. 1,” Cutlip said. “The Blowing Rock School playground is No. 2.”

Finding Creativity

In designing his garden and landscape architecture projects, Cutlip takes to heart what Thomas Church once said, “The only limit to your garden is at the boundaries of your imagination.”

For Cutlip, the “land whisperer,” each “blank canvas” always has something to say and how it communicates may take many forms. It could be a sharply etched ravine down the bald face of a granite boulder, seeming to beg for water whistling again down that carved out pathway. It could be a school playground, where he asks every student in school to write down on a piece of paper the thing they would most like to see in a new playground — and then incorporate those thoughts in the final design. Or, it could be a rock wall dating back to the 1600s, tediously crafted by human labor before machines were able to move and lift the stone — a wall now preserved to frame a golf course hole in Narragansett, Rhode Island.

“I listen to what the land is saying and do my best to bring out its beauty,” Cutlip said in concluding his Blowing Rock Garden Club lecture.